World’s turtles face plastic deluge danger

An international study led by a University of Queensland researcher has revealed more than half the world’s sea turtles have ingested plastic or other human rubbish.

The study, led by Dr Qamar Schuyler from UQ’s School of Biological Sciences, found the east coasts of Australia and North America, Southeast Asia, southern Africa, and Hawaii were particularly dangerous for turtles due to a combination of debris loads and high species diversity.

“The results indicate that approximately 52 per cent of turtles world-wide have eaten debris,” Dr Schuyler said.

The study examined threats to six marine turtle species from an estimated four million to 12 million tonnes of plastic which enter the oceans annually.

Plastic ingestion can kill turtles by blocking the gut or piercing the gut wall, and can cause other problems through the release of toxic chemicals into the animals’ tissues.

“Australia and North America are lucky to host a number of turtle species, but we also therefore have a responsibility to look after our endangered wildlife,” Dr Schuyler said.

“One way to do that is to reduce the amount of debris entering the oceans via our rivers and coastlines.”

A previous study by Dr Schuyler and colleagues showed that plastics and other litter that entered the marine environment were mistaken for food or eaten accidentally by turtles and other wildlife.

The risk analysis found that olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) were at the highest risk, due to their feeding behaviour and distribution.

Olive ridley turtles commonly eat jellyfish and other floating animals, and often feed in the open ocean, where debris accumulates.

This research echoes the results of a similar study on seabirds published two weeks ago by CSIRO collaborator Dr Chris Wilcox and colleagues, which found that more than 60 per cent of seabird species had ingested debris, and that number was expected to reach 99 per cent by 2050.

“We now know that both sea turtles and seabirds are experiencing very high levels of debris ingestion, and that the issue is growing,” Dr Wilcox said.

“It is only a matter of time before we see the same problems in other species, and even in the fish we eat.”

The study, published in Global Change Biology, involved UQ’s Dr Kathy Townsend and researchers at CSIRO Hobart, Texas A&M University, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Honolulu, University of NSW, and Imperial College London, UK.

It was part of an Australian Research Council Linkage project supported by Earthwatch Australia, CSIRO, Healthy Waterways and Australia Zoo.

Media: Dr Qamar Schuyler, q.schuyler@uq.edu.au, +61 427 566 868.

Related articles

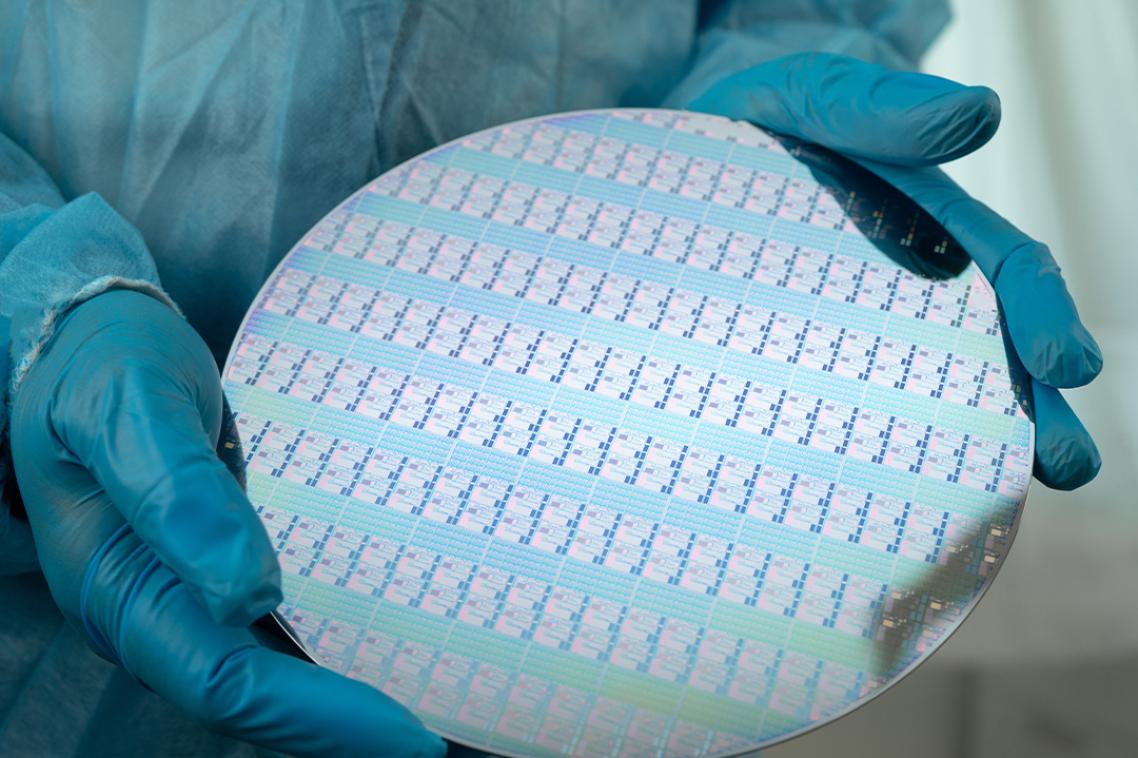

Superconducting germanium made with industry-compatible methods

Under the surface: how genetics could save the Great Barrier Reef

Media contact

UQ Communications

communications@uq.edu.au

+61 429 056 139