World’s protected areas being rapidly destroyed by humanity

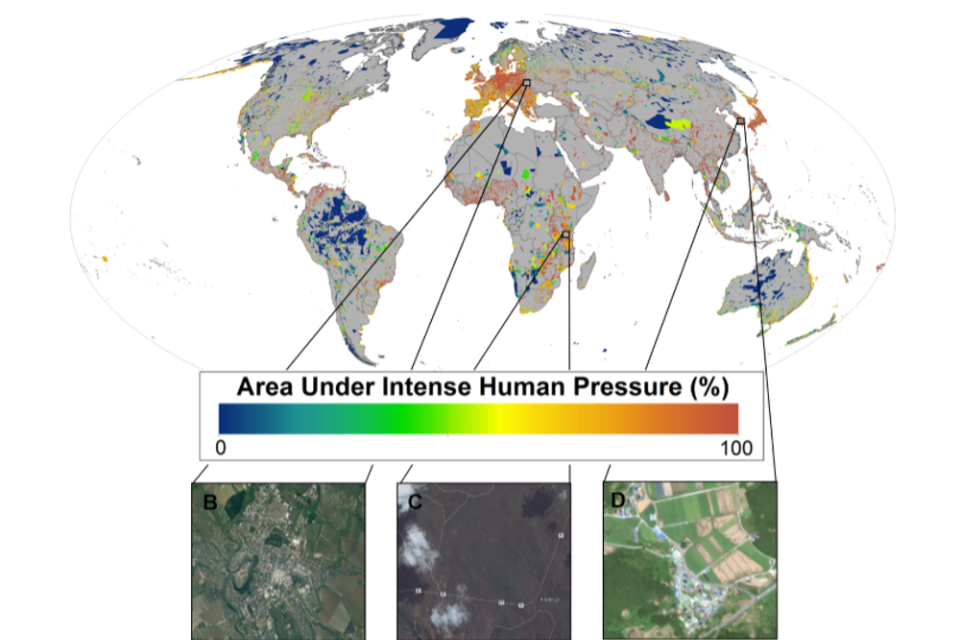

One-third of the world’s protected land is under intense human pressure, according to an international study described as ‘a stunning reality check’ on efforts to avert a biodiversity crisis.

The University of Queensland-led research has found six million square kilometres of protected land – equivalent to two-thirds the size of China – is in a state unlikely to conserve endangered biodiversity.

PhD candidate Kendall Jones said in some cases the scale of damage was striking, with the greatest impacts found in heavily populated places including Asia, Europe and Africa.

“We found major road infrastructure such as highways, industrial agriculture, and even entire cities occurring inside the boundaries of places supposed to be set aside for nature conservation,” Mr Jones said.

“More than 90 per cent of protected areas, such as national parks and nature reserves, showed some signs of damaging human activities.”

UQ Professor James Watson, a Wildlife Conservation Society research director, said the study clearly showed nations were overestimating the space available for nature inside protected areas.

“Governments are claiming these places are protected for the sake of nature when in reality they aren’t,” Professor Watson said.

“It is a major reason why biodiversity is still in catastrophic decline, despite more and more land being protected over the past few decades.”

The study used the most comprehensive global map of human pressure on the environment, the Human Footprint, to analyse human activity across almost 50,000 protected areas.

Large, strictly protected areas were under far less human pressure than smaller protected areas where wider ranges of human activities were permitted.

Professor Watson said well-funded, well-managed and well-placed, land protection areas were extremely effective in halting threats to biodiversity loss and ensuring species return from the brink of extinction.

“There are also many protected areas that are still in good condition and protect the last strongholds of endangered species worldwide,” Professor Watson said.

“The challenge is to ensure those protected areas that are most valuable for nature conservation get the most attention from governments and donors to ensure they safeguard it.”

Mr Jones said all nations need to be honest when accounting for how much land they have set aside for biodiversity conservation.

“It is time for the global conservation community to stand up and hold governments to account so that they take the conservation of their protected areas seriously,” he said.

The study, involving UQ, the Wildlife Conservation Society and the University of Northern British Columbia, appears in the prestigious journal Science.

Media: Professor James Watson, james.watson@uq.edu.au, +61409185592; Kendall Jones, kendall.jones@uqconnect.edu.au, +61401920530.

Related articles

Decades of surveys show whale migration shift

Should you consent to your doctor using an AI scribe? Here’s what you should know.

Media contact

UQ Communications

communications@uq.edu.au

+61 429 056 139