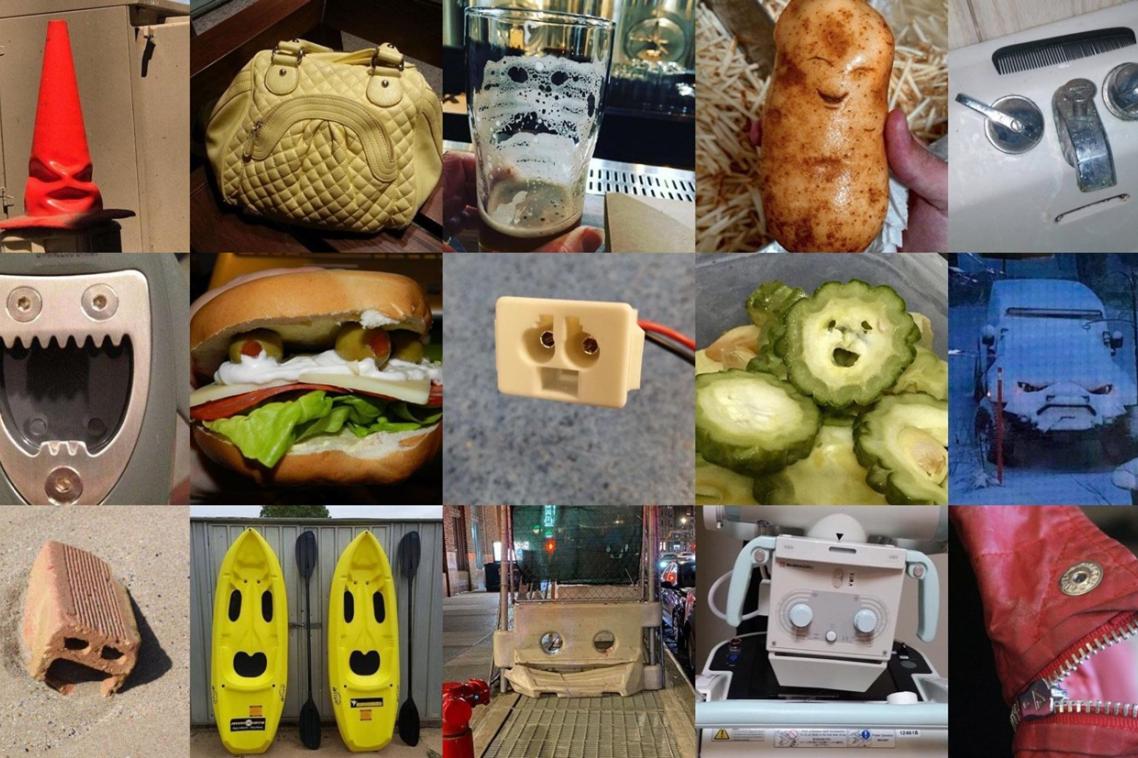

The brain science behind how we see faces in objects

(Photo credit: The University of Queensland and Susan Wardle/National Institutes of Health. )

Two eyes, a nose and a … tree trunk. The human brain can sometimes see faces in objects faster than recognising the objects themselves, a University of Queensland study has found.

Dr Amanda Robinson from UQ’s School of Psychology led a study that investigated face pareidolia – a phenomenon where people see faces in inanimate objects – and found the human brain detected faces 90-130 milliseconds after looking at an object, and categorised it within 150-210 milliseconds.

“We found there were two stages of brain processing – the initial neural response detected faces, and then there was a dramatic shift to recognise the objects,” Dr Robinson said.

“The brain is processing the faces and objects at different times, but we believe this process could also be happening in parallel in different areas of the brain.”

Dr Robinson said previous studies had explored the perception of illusory faces, but this was the first time the team had explored how the brain processes and categorises faces in objects.

“When we look at something we might see a face, but our brain also knows it isn’t a real human face.

“We wanted to explore exactly how these processes occur in the human brain, and how we differentiate between a face and an object.

“Our brains know faces are important because they’re vital for social interactions – we talk to people all the time, we see our family members and friends, so it’s understandable that our brains are wired to detect faces in the wild.

Researchers undertook 3 behavioural tasks where participants were shown images of illusory faces. In one task, more than 380 people were shown 3 images of real faces, faces in objects and regular objects, and were asked to pick the odd one out.

Associate Professor Jess Taubert said they wanted to see if face perception emerged, even if people weren’t asked to look for faces.

“The results from this task showed people perceived faces in objects as its own separate category compared to real faces and objects,” Dr Taubert said.

“In another task where people were asked to rate how like a face was, we found people rated the illusory faces more as a face than an object.”

Researchers also used electroencephalography (EEG) in their study to look at people’s brain responses to stimuli.

“Results from this showed face-identity signals persisted even after the brain had identified the objects, which shows the brain preserves initial interpretations rather than overwriting them,” Dr Taubert said.

“This provides critical insight into the brain’s capacity to build and maintain multiple independent representations in parallel.

“For example, if you need to judge how face-like an eggplant looks, you can, while also recognising that an eggplant is a vegetable.”

The research is published in Communications Psychology.

Topics

Related articles

Do you see faces in things?